|

Iglesia Santa Maria de Los Angeles, Barrio Riguero.

Iglesia Santa Maria de Los Angeles, Barrio Riguero.

This mural reflects the support shown by Nicaragua's progressive Catholic clergy for the

Sandinistas "preferential

option for the poor," known also as "the logic of the majority."

On the other hand, Pope John Paul II was not at all happy with these progressive priests, primarily

because their open advocacy of the empowerment of the poor might also someday lead to the poor questioning papal

authority.

Indeed, during his March 4 stopover in Nicaragua as part of his 1983 Latin American tour, John Paul publically

rebuked Catholic priest and Sandinista Minister of Culture Ernesto Cardenal, who had remained in the government

in disobedience of his Archbishop, Obando y Bravo. Sandinista leaders were waiting to greet him at the

airport, and as Cardenal kneeled to kiss the Pope's ring, John Paul withdrew his hand, saying

"You need to correct your situation with the Church". (Kinzer, Blood of Brothers, p. 201.)

As the Pope had promised, he made no political statement, meaning that he did not mention, nor condemn, Reagan's

atrocious war against the peasantry he purportedly loved so much. This omission was quite reasonably

interpreted as

support for the war, as Ernesto Cardenal trenchantly observed later: "It has been said that the Pope is very

thankful to the CIA for the work it has done in Poland, and that the Pope has come to repay the CIA in

Central America." (Kinzer, ibid., p. 202.)

In 1985, John Paul also elevated the contras' own religious mentor, Obando y Bravo, to Cardinal.

(Kinzer, ibid., p. 298.)

|

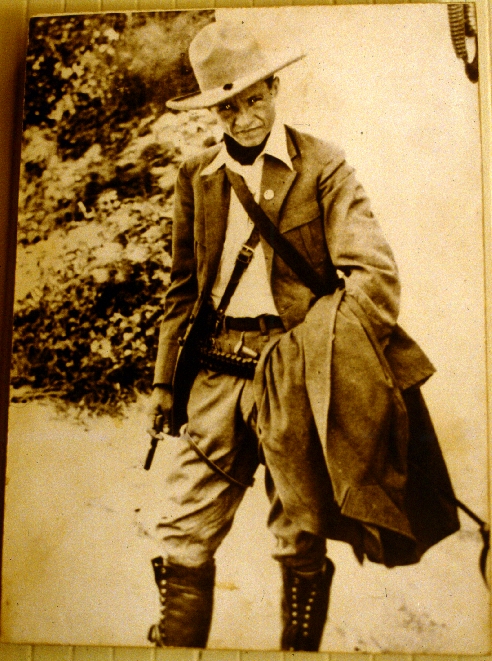

Augusto Sandino.

Augusto Sandino.