|

Wednesday, January 1, 1986

Wednesday, January 1, 1986

Today we went swimming. I don't have the name or location of this river.

Honduras is definitely out of the question, and we are not sure whether we will be allowed into El Salvador.

Nevertheless, Ron and Katherina are now in the northern Nicaraguan port

of Corinto, trying to charter a boat that will take us to El Salvador, or to Guatemala, or to

Acapulco if Guatemala will not let us in. In fact, Guatemala immigration has denied us entry.

The Salvadoran committee has asked the march to send a few people to be with them as they create their own

March for Peace. We decide to send 10 people to El Salvador. This was risky business for those who went.

I was not one of them, and will present what

information I was given by Sonja Iskov, along with her photos, on the El Salvador page.

On an earlier page, I said that I had earlier assumed the role of creator and enforcer of certain toilet

protocols necessary to prevent the overloading of old sewer pipes in southern Nicaragua.

Yesterday I had gathered together a crew to handle our portable toilets: Tom (Norway?, Sweden?); Tom (USA);

Geir; Unud(?); Live; Kirsten; Dean; Steven, Richard.

I assume that we were doing our best, but for some unnoted reason, I again had to give my fastidious

co-marchers a stern talking-to:

"People who use the toilet are responsible for its maintenance. This means that monitoring the toilet is

everyone's responsibility. If you see that the toilet is full, get someone to help you move it out, and replace

it immediately with a spare at the end of the building.

"Then take the full toilet over to the large pit 40 feet to the north of the building and set it on the ground.

Send someone to look for me immediately upon replacing the toilet. Your job is then finished."

I'm sure that my scolding had its intended effect, as my notes don't show that I had to assert myself again.

|

Saturday, December 28.

Saturday, December 28. Something has stopped us in our tracks.

Something has stopped us in our tracks.

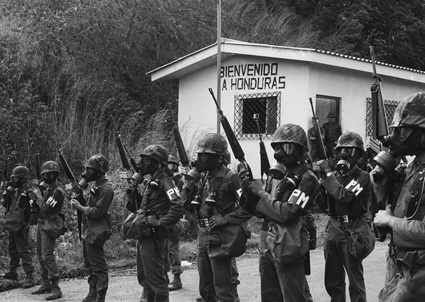

Welcome to Honduras.

Welcome to Honduras. We displayed Old Glory—really Old Glory.

We displayed Old Glory—really Old Glory. In spite of our disappointment, we are in high spirits as we return to set up camp at what will be be our

home for the next 6 days—Escuela Olman Flores E. Sonis (Somis?), serving the small

village of La Playa, not far east of El Espino.

In spite of our disappointment, we are in high spirits as we return to set up camp at what will be be our

home for the next 6 days—Escuela Olman Flores E. Sonis (Somis?), serving the small

village of La Playa, not far east of El Espino.  La Playa proper must have been somewhere else, because I don't recall any concentration of homes or shops

in our neighborhood here.

La Playa proper must have been somewhere else, because I don't recall any concentration of homes or shops

in our neighborhood here.  The following photos, mostly undated, show our activities over the next several days.

We returned to the border

every day.

The following photos, mostly undated, show our activities over the next several days.

We returned to the border

every day.

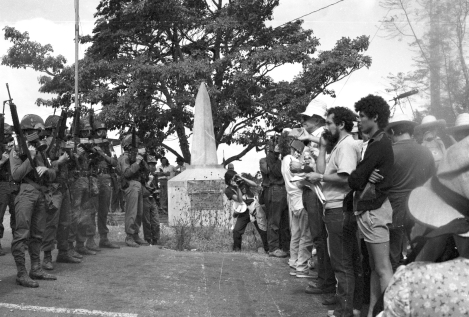

The obelisk marks the border.

The obelisk marks the border. All the world is watching.

All the world is watching. As we had done at the Howard Air Force base in Panama, each of us requested permission to enter Honduras.

Here Margaret shows her passport to the Cobras.

As we had done at the Howard Air Force base in Panama, each of us requested permission to enter Honduras.

Here Margaret shows her passport to the Cobras.  Harald displays the Norwegian flag to the Cobras in the hope that Norway's peaceful spirit will

inspire them to allow us into Honduras. No luck.

Harald displays the Norwegian flag to the Cobras in the hope that Norway's peaceful spirit will

inspire them to allow us into Honduras. No luck. We were greatly privileged to be accompanied by two Argentine women, members of the

We were greatly privileged to be accompanied by two Argentine women, members of the

Here we all show our passports, to no avail.

Here we all show our passports, to no avail.

Blase presides at an ecumenical Sunday morning service on December 29th.

Blase presides at an ecumenical Sunday morning service on December 29th.

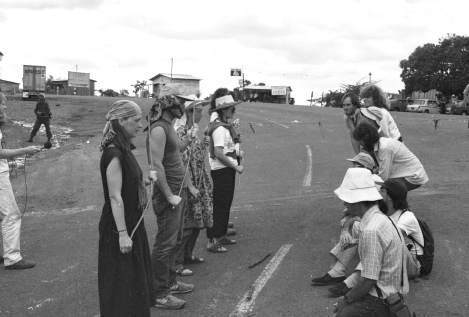

Torill has rejoined us after her unsuccessful efforts to get us into Honduras. Here, in the

Nicaraguan customs station destroyed by the contras, she fills us in on the details. Margaret, the American

woman living in Costa Rica, stands to Torill's right, perhaps acting as translator for our Central American

friends.

Torill has rejoined us after her unsuccessful efforts to get us into Honduras. Here, in the

Nicaraguan customs station destroyed by the contras, she fills us in on the details. Margaret, the American

woman living in Costa Rica, stands to Torill's right, perhaps acting as translator for our Central American

friends. We entertain the troops. Bob Hope would have been proud of us.

We entertain the troops. Bob Hope would have been proud of us. Impromptu dancing was a favorite way of passing the time. Here, Grethe and a Dane whose name I don't have

provide the music. Richard from Wisconsin reclines on the pavement.

Impromptu dancing was a favorite way of passing the time. Here, Grethe and a Dane whose name I don't have

provide the music. Richard from Wisconsin reclines on the pavement.

Monday, December 30.

Monday, December 30. Tuesday, December 31st.

Tuesday, December 31st.  Some local kids. Date uncertain. Janet in the background.

Some local kids. Date uncertain. Janet in the background.

Wednesday, January 1, 1986

Wednesday, January 1, 1986 Date uncertain, but after the 30th.

Date uncertain, but after the 30th. Thursday, January 2.

Thursday, January 2. We reach out to the Cobras, in the spirit of peace and friendship.

We reach out to the Cobras, in the spirit of peace and friendship.

The Cobras are unresponsive, so we stage a peaceful sit-in.

The Cobras are unresponsive, so we stage a peaceful sit-in.

Finally, we win the hearts of the Cobras.

Finally, we win the hearts of the Cobras. Friday, January 3.

Friday, January 3. Monday, January 6.

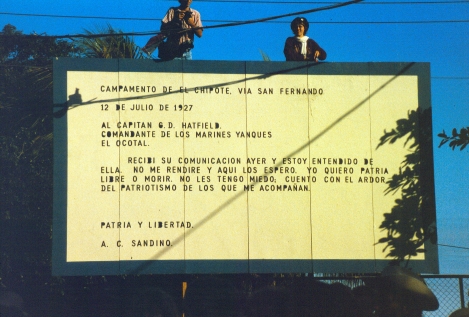

Monday, January 6. The preceding picture was taken from the top of this billboard. It's clear that the Sandinistas had a sense of

humor—they could

not resist confronting our diplomats—and the spooks who used the embassy as cover—with Sandino's

response to Marine Captain Hatfield, who had apparently threatened to send his troops against Sandino

if he did not surrender.

The preceding picture was taken from the top of this billboard. It's clear that the Sandinistas had a sense of

humor—they could

not resist confronting our diplomats—and the spooks who used the embassy as cover—with Sandino's

response to Marine Captain Hatfield, who had apparently threatened to send his troops against Sandino

if he did not surrender. Tuesday, January 7.

Tuesday, January 7.